By Dr. Joseph A. Henderson, Environment & Society Department, Paul Smith’s College

I grew up around guns. My father is a hunter and taught me to respect guns from a young age. I have fond memories of walking through early winter woods with my dad, spending time together and talking. (We weren’t actually very good at hunting.) Later, when I worked for the DEC summer camps program, I taught hunter safety courses alongside ECOs. Our guns were relatively simple machines: single shot bolt and break-actions, and still capable of doing their deadly job. This was one type of gun culture, and one I suspect many of you may be familiar with: relatively simple technologies for the expressed purpose of hunting and marksmanship. But there are other gun cultures, and we cannot understand them without looking at broader changes in American social patterns.

In my anthropology class here at Paul Smith’s (SOC 300) we examine culture as the “collective processes that make the artificial seem natural” (Welsch & Vivanco, 2016, p. 29). Such processes include the symbols, values, norms, and traditions that support daily practice. Anthropologists like myself who study American culture and subcultures understand our current moment as shaped by the cultural and political norms of neoliberalism, an economic ideology that both major political parties began experimenting with in the late 1970s. Neoliberal ideas involve reworking government and other public spaces away from common goods and toward individual market participation. Rather than having a society with regulated markets, we have become a deregulated market society.

You experience neoliberalism in two major areas of your social life: education and health care. In the United States, educational debt is increasingly an individualized phenomenon with you, the individual, shouldering more and more of the financial risk as student debt. Similarly, health care primarily exists as an individual commodity and, if you remember from the Obamacare debate, is framed as a market product that people are forced to purchase among a set of market choices. In both cases, the duty to secure a public good is privatized, with the individual forced to bear the burden of responsibility. The social result, as the political scientist Wendy Brown details in her book Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution, is that “the political itself is rendered in economic terms, [and] the foundation vanishes for citizenship concerned with public things and the common good” (2016, p. 39). Said another way, we are increasingly forced by government policies to become individual agents, seeking only to maximize our own individual good. It is helpful to remember that other countries (e.g., Finland) structure their societies differently, and use government to provide for the common good in addition to the individual good, a point I shall return to in a moment.

Gun cultures exist within this larger social and political terrain as well, and we can see how neoliberalism shapes the confines of the debate. We have – as a collective society – determined that one’s ability to exist is now largely an individual affair. This is the cultural logic behind “stand your ground” laws and the fetishization of an individual right to bear arms in all places and at all times. In Citizen-Protectors: The Everyday Politics of Guns in an Age of Decline the sociologist Jennifer Carlson (2015) detailed how guns made sense as a means of maintaining social power in an increasingly precarious society shaped by neoliberal policies and the decline of shared social goods. Surrounded by a decaying social and economic fabric and the fear of a precarious future that that produced, the participants in Carlson’s research reached for guns as a technological means of maintaining their individual social status. This was especially true when participants perceived threats to their position in racial and gendered hierarchies. Guns gave them a sense of power and allowed them to maintain identity in an otherwise shifting social and economic order.

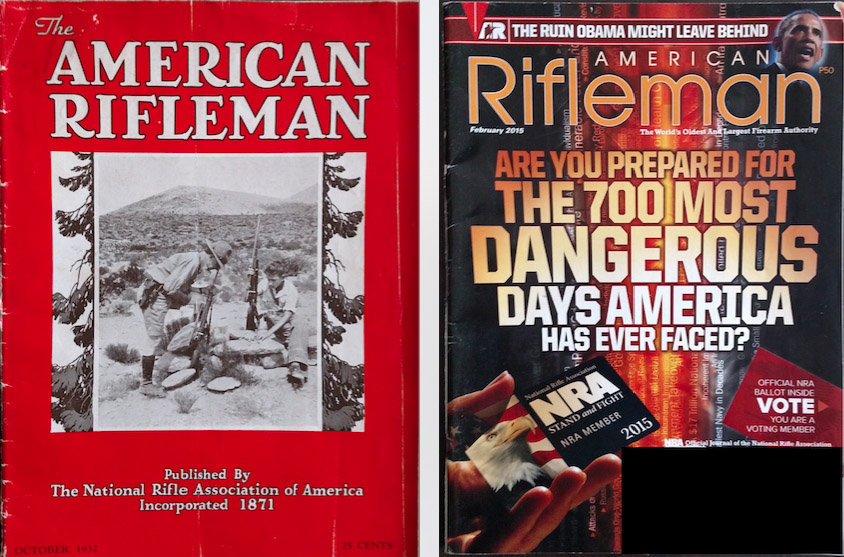

My father, a lifetime National Rifle Association member, was once satisfied with owning simple weapons for hunting game and the occasional plinking session in the backyard. He now owns a handful of military grade weapons that sit largely untouched in a gun cabinet. Surrounded by increasingly apocalyptic NRA magazine artifacts that stoke a sense of impending societal collapse, my father stews with a sense of cultural aggrievement and is now terrified of a world that he perceives as rapidly changing around him. This has become his new gun culture, and it too is one that I suspect some of you are familiar with. It is helpful to note that the NRA began in 1871 as an organization concerned with increasing the marksmanship skills of its members and to promote hunting, but became much more politically charged around the same time that neoliberal economic policies were being implemented in the 1970s. NRA-produced media changed around that same time and moved toward an argument that 1) the world was increasingly scary and 2) that it was an individual’s right to protect themselves, their family, and their property (Spitzer, 2017). Sound familiar?

It turns out that symbolically stoking cultural fear also works great for selling lots of guns to an increasingly scared subset of the population. However, after spiking during the Obama Administration, overall gun sales have fallen since President Trump’s election win last year, prompting some in the industry to warn of a “Trump Slump” in gun profits (Yablon, 2017). Gun owners, largely buoyed by wins in the last election, apparently no longer feel the need to bolster their social positions via gun consumption. The American civilian gun industry is a 51 billion dollar a year enterprise (NSSF, 2017). Social scientists and public health researchers estimate that there are over 300 million guns in active circulation in our country, but that fewer people are owning more and more guns (Pew Research, 2017). In order to keep making profits, gun companies have had to accessorize, offering ever more complicated specializations to a decreasing pool of consumers. My father now owns military-grade technology not because he actually needs it, but mainly because he doesn’t want anyone to set any limits on his freedom to consume whatever he wants, whenever he wants. Don’t tread on him, if you will. In this way he has become a fully neoliberal subject, working only to maximize his own individual sense of consumptive freedom, the rest of society be damned.

Other countries do not structure their societies in such an individualized fashion and instead take a policy approach geared more toward securing freedom as a broader public good. Japan, for example, sets strict legal parameters around gun ownership, including mandatory training courses with exams, registration with community police agencies, extensive mental health and background checks, and periodic home inspections. In 2015 Japan had exactly one non-suicide gun death. During that same time period the United States tallied more that 13,000 (Denzer, 2017). Japan has a more communal society that dedicates public monies toward shared health care and educational systems, with the broader society sharing responsibility for the well being of their neighbors. Japanese citizens simply do not live their lives with the same sense of neoliberal precarity that structures much of our lives in modern America. We might want to consider other definitions of freedom as part of our larger gun culture conversation.

The Constitution of the United States allows individual states leeway over how they control the flow of gun technologies within their political borders, and this is supported by major Supreme Court decisions. The late conservative Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, who wrote for the majority in DC v. Heller and later supported the argument in McDonald v. Chicago, argued that while the right to own a firearm was an individual right, it is also within the purview of individual states to determine how to regulate gun technologies for the sake of the common good. He stated, “Like most rights, the right secured by the Second Amendment is not unlimited” and that it is “not a right to keep and carry any weapon whatsoever in any manner whatsoever and for whatever purpose” (2008, p. 2). New York State, for example, has implemented stricter gun legislation and as a result has one of the lowest gun death rates in the United States (CDC, 2016). We, as a body politic, need to decide how we are going to shape our shared American culture. Are we a country where everyone is like who my father has become: someone out only for their own limited protection? Or do we care about something bigger—a broader sense of shared freedom that exists beyond ourselves? We, including all of us here at Paul Smith’s College, need to figure out what kind of world we want to have.

I used to see my father as a responsible gun owner, and maybe at one time he was. But I no longer view him this way, and this pains me greatly. He simply refuses to make any kind of sacrifice toward a larger civic good and views any such request as an affront to his narrow view of liberty. I wonder what might move him to feel less fearful and alone. What might make him broaden his understanding of freedom to include others, including his extended family? What would it take for him to understand that his grandchildren’s freedom to go to school or play in a park without the threat of gunfire is more important than his freedom to own a military-grade weapon that he never uses? I do not know the answers to these questions, and I struggle with them daily. Regardless, recent polling shows that a majority of gun owners support responsible gun legislation (Monmouth University, 2018). The cultural politics in this country may be shifting away from a narrow neoliberal understanding of civic participation and toward something where we again think of our obligations toward one another, regardless of cultural background or political preference.

My initial response after reading this well composed screed was disgust. Disgust at the attitude shown to our second amendment and the writers willingness to belittle his father for his beliefs.

I feel compelled to respond.

This article is wrong in so many ways. It is textbook anti-gun. It is slanted and only presents a one-sided emotionalized viewpoint with cherry picked statistics. The writer reflects a insular viewpoint.

Quite possibly these viewpoints are applicable in an academic mono culture but they don’t reflect the reality of the world I know and live in.

Japan might have a lower suicide rate by firearm than the USA but it has the 5th highest suicide rate in the world as of 2017. Higher than the USA, so what is the purpose of using that statistic other than to falsely slant the truth in favor of the writers argument.

The writer cites other countries that have banned or restricted firearms. What he neglects to clarify is how this was done and the response of the population. They all regret the loss of a right once it was gone.

It is up to the individual to defend themselves lawfully. A weapon allows that. It is the equalizer that allows a person to preserve their life and loved ones life. Concealed carry holders are the MOST law abiding segment of society. It is a right enshrined in our constitution by the second amendment and to go further a duty of all Americans to exercise lawfully.

I can understand the attitude of the writers father on wanting to exercise his constitutional right. It is under attack. I’m certain he understands that all gun crime is stopped by a “good guy” with a gun and views himself as one of the good guys.

There are several real life instances where after natural disasters the population had to defend life and property by the use of firearms. This is what the writers father understands and is comforted by his ownership. You can’t reason with unreasonable people.

Unfortunately the writer has the aura of legitimacy due to his education and position. Unfortunately also for his audience that does not take the place of real life experience or reality.

I am not against legal carry. I am against criminal carry.

Thanks for the thoughtful comment.

I too agree that this is a well written article but part of the story that needs to be focused on is the fact that the writer and his father were both taught respect for firearms. This writer spent quality time with his father learning that guns are not toys and how to value life with not always “making a kill” while hunting. Hunting was just a way to spend time together. In today’s society a large portion of our population is deprived of a father. Many young men have no elder to spend quality time with to learn respect for themselves or others around them and how to be held accountable for their actions. The moral,social and cultural breakdown in our society should be a larger concern than is being reported across the country. The writer does touch on this saying his father “doesn’t cares for the larger civic good.” Maybe his father doesn’t see that there is a larger civic good anymore. It is neoliberalizm that has dismantled the basic structure of families. Policies that encourage and enable single parent homes only caring for the individual instead of nurturing families(the larger civic) to care for each other.

This is just my opinion after all. Everyone has the right to express their thoughts and through these crazy political times we are living in I applaud Paul Smith’s College for allowing all opinions to be voices.

I feel like you missed the entire point of the article. Wasn’t it about markets being a controlling force in our decision making ? The expanse of political and economic persuasiveness permeating our psyche? Forcibly? Maybe that same expansiveness needs to needs to be thoughtfully practiced when we read sociological theory.

I’m a thoughtful, unpersuaded gun owner (and user).

Excellent piece combining personal narrative, a sophisticated analysis of culture, and a reflection on our current socio-economic situation. Bravo! I’ve added it as an update to a post I wrote on Gun Culture.