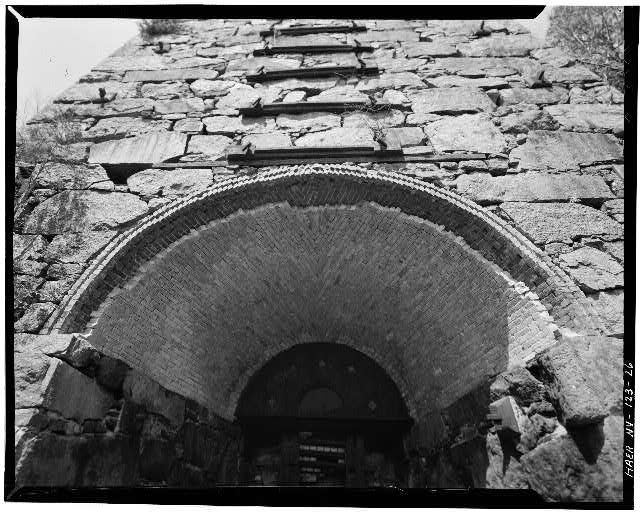

Pictured Above: Tahawus furnace. Jack Stacey created a video on Adirondack Iron, which will be featured in The Apollos soon.

As I write this, I’m looking at two small lumps of bituminous coal sitting on my desk. I think I may have been the only kid in my town that would have been happy getting coal for Christmas.

I’ve always had a connection to mining, ever since I learned from my father that my ancestors left Poland to find work in the coal fields of Pennsylvania. My great grandfather, Joseph Stacey, operated a dragline shovel, pulling from the Earth a resource so vital to the growth of this mighty nation. I can envision my great grandfather at the helm of his mammoth Bucyrus-Erie shovel, loading coal that would eventually be destined for the vast railyards of the Pennsylvania Railroad, loaded aboard hoppers being pulled by a fire-breathing J1 class “Texas” locomotive, and shipped out to keep the home fires burning — literally.

The story of mining in the Adirondacks, however, is one not told with coal, but with iron. The word itself — iron — conjures up images of the days when America was an emerging superpower, fueled by steam, steel, and muscle. The Adirondacks were essential to producing this raw material, which was so coveted by our resource-hungry nation. We have a history up here that is untold in the history books.

Question for the reader: what do the Golden Gate Bridge, the George Washington Bridge, and the Brooklyn Bridge all have in common?

Adirondack iron.

Our connection to these iconic symbols of the United States is one that is slowly disappearing. Most of us come to the Adirondacks to recreate, to enjoy an early morning paddle on a glassy lake as the fog rises from the water’s surface, to experience the scenery that cannot be found elsewhere in the world. We don’t give a thought to the legions of men that toiled in dirty, cramped, and downright dangerous conditions. We drive through small towns such as Standish, Tahawus, and Mineville, without a second thought to the men who built them. They are but a dot on a map, letters on a weather-beaten road sign, names that only hold significance in volumes of books that remain untouched and dust-covered in a forgotten corner of a bookcase.

Yet they are so much more.

They are our legacy, our heritage. They are our roots as Americans. We mustn’t forget the Adirondacks wasn’t always a place to lace up your $150 Keen hiking boots, or to back your Chevy Tahoe up to the boat launch for a cruise on the lake to catch that monster fish. It was a difficult place, a place where men gave their all — sometimes their lives — to support their loved ones and their nation. The rich history of mining in the Adirondacks is one that lives on through families of miners and the cavernous ruins that stand silent in the face of an uncertain future.

So if you walk through the scarred landscape of the mine at Lyon Mountain, where the only signs of life are the tissue-paper-winged locusts skittering across the dry ground, think of the men that arrived here to start their day under the ground. When you traipse the empty hoist room, the only sound being the echo of your footsteps off the cold cistern-like walls, or the slow drip of water from a darkened, far-off corner of the powerhouse, think of the men that immigrated to a foreign country only to be discriminated against and mistreated — men like my great grandfather — all the while performing backbreaking labor. In a place that is now home to fields of Queen Anne’s lace and chicory, blanketing the ground as if to heal it from decades of industrial disfigurement, think of what its history means to you.

When not playing guitar in a style similar to that of his heroes Carl Perkins and Grady Martin, Stacey spends his time researching historical points of interest. Growing up in the shadow of the Valley of Opportunity, an area rich in history and architecture, his hometown of Binghamton, New York inspired him to begin advocating for the preservation of historic structures. He strives to connect the past and present by helping preserve the little-know legacies of small towns.